From the barn behind his house I watched him talking with his wife in their kitchen, and the light from the candles gripped to him as he laid both hands flat on the table and bent his head and spoke, and the yellow light slid onto her as she went to him and grasped him, she was speaking to him urgently, and after a while he turned and took her in his arms and I felt it, I felt it in every part of me but most of all where I would if I was a woman, I held myself there and I heard a wave sighing, but I heard it from far away where the grey sea licks the coast.

And when his Lady died he came crashing out onto the moor to find us and I cried and tried to hide myself but he held an arm up against the rain and he could see us, and as he spoke I felt the thick tide press against my skull and pull away, pulling my hair with it, my hair like rats’ tails thin and wet.

I saw the small kirk he went to when he was little and the winds that battled against it like the ones beating against him now, and I saw the bladed corn move in its small way and he sat among it and sucked on it and I saw it all crumble and slide past his ears, the bricks from the church, the sweet little seeds of corn, everything as bloody as bedsheets, and now his body rose up tall and proud against the purple sky, and I wished I was a woman.

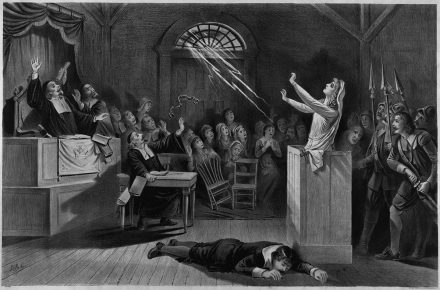

Then we pulled his proud body up slick and red and headless from our cauldron and he went pale when he saw it, and we pulled seahorse babies out of our torn stomachs and the blood ran towards him and he thought he was going to drown and he screamed filthy hags, his eyes red and hating, and sister said come, cheer we up his sprites, our king. So we danced around him and they screamed his name but I was quiet, I held his name in my mouth and tasted it so I could pretend we were alone together, like I had been alone with him and his wife, and as I passed him he reached out his fingers and caught my hip, speak if you can, he said.

And long after he’d gone I felt the ghost of his fingertips on me, and I was burning and alive where he’d touched me, I ached, and we danced in the mud and the blood, and the day of the battle was red as well, but dry, and I slipped away from them and slid along the ground beneath him and his feet trod into me, my body not dry but wet as the lips of a bog. And when he stumbled into a copse, tired and bleeding, his hand on his side, I followed him, and he turned and saw me. I stood in front of him.

From above his wide shoulders he peered down, and I pulled him into me, he was pouring out blood and my skin drank it in like a cup, I held him, and on the ground his body hovered above mine and he raised his head and blinked quickly at the sky. His arm was heavy and he mumbled things and stroked my hair and I knew he thought he was in bed with his wife. And then I told him it was time to find Macduff, so he sat up and followed me quietly out of the trees. There were children dancing on the field and Macbeth stared at them, I saw him remember. And he looked at me and his face twisted and he saw who I was and he hated me again, I knew that he’d gone. The leaves crackled under our feet. The white air was thick on the ground, and Macduff waded out of it and cut the king down, and his blood spread out and made the field a red lake, he was still blinking quickly at the sky.

Issy Macleod