Rebekah Wright and Nick Miao

To protect anonymity, some interviewees in this article have been given pseudonyms from the musical Rent.

London is famously the most expensive city in the UK. A decent standard of living can cost up to 58% more than in the rest of the country and if you’ve ever lived in UCL halls or private rental accommodation you’ll know that the word ‘decent’ can be used very, very liberally.

The London rental market has spiralled into exorbitance, as eleven London boroughs have seen rent soar by over 30% since 2021. More recently, the director of SpareRoom has said that the market has ‘reached a point where it’s not really working for anybody.’

But all of this overshadows an equally severe crisis in student accommodation. Unipol, a student housing charity, has described the situation as at a ‘crisis point’ and the National Union of Students (NUS) described the student housing market as ‘broken’. Meanwhile, the higher education think tank HEPI warned that, ultimately, student homelessness would increase as a result of the cost of living crisis.

UCL students are forced to face skyrocketing rent prices both in the private rental market and in UCL halls, where the average room price has risen by 44% since 2016, consuming a sizable chunk of a full student maintenance loan.

The newest UCL hall, One Pool Street (OPS) at the UCL East campus charged £254 per week in 2022/23 which has risen to £282 a week in 2023/24. One resident, Mimi, told The Cheese Grater that living in OPS was not worth the rent charged. ‘[It] isn’t as expensive as ensuite rooms at other halls like Astor’, she acknowledged, ‘but we had the cost of travelling’.

The dramatic hike in rent at OPS does seem particularly unfair given that it’s in Stratford, a 45 minute commute away from Bloomsbury. Seemingly the management at UCL accommodation neglected to consider that the majority of students who still study on the main campus will also have to pay significant travel fees to TfL atop their rent. Mimi estimated that commute money for her was ‘easily well over £500 for the whole year’.

Alongside the travel fees, Mimi also mentioned that the OPS’s distance from every other UCL hall made it ‘harder to socialise’. That, coupled with ‘the single beds and tiny rooms’, meant that the £254 a week she paid for her space was disproportionate to how much she valued it.

‘Everything at OPS annoyed me. I hated it all – especially the commute,’ she told us, ‘I paid to live in halls, so why am I doing a longer journey than (some) people who live at home?’ Despite the disadvantages of OPS for students who study in Bloomsbury, UCL has still raised the rent by almost £30 per week since 2022.

UCL’s rent increases are also disproportionate to that of other student accommodation providers. Rent increased by an average of 11% in UCL halls between 2022 and 2023 but Unite Students, the largest provider of private student accommodation in the UK, only raised rent by 7%.

It’s evident that rent prices were raised dramatically by the UCL administration, particularly from 2022 to 2023. However, whilst some increases may come across as too substantial for what the accommodation is worth, it is true that UCL are not entirely to blame, as rent increases do seem unavoidable in the wider context of Britain’s housing crisis.

Still, most students rely on student loans, part-time jobs and support from parents or guardians to fund their time at university. The escalation in UCL accommodation prices adds an extra squeeze to the wallet of a student living in the UK’s most expensive city.

This is easily observable as the average rent in UCL halls fails to meet the NUS’ standard for affordable accommodation, which is set at under 55% of the full maintenance loan. In an internal SU briefing on the cost of living obtained by The Cheese Grater, the Union notes that, as of 2022, the average cost of rent in London would ‘consume 88% of a full student maintenance loan’.

For students that are struggling with wellbeing, whether that be due to accommodation-related issues or otherwise, Student Support and Wellbeing (SSW) is relatively well publicised at UCL. When we asked Mimi if she knew who she could turn to if the stress of essentially being a commuter ever became too much she was well aware of the wellbeing support on offer and named the two student advisors from her course. Another student we asked, Joanne, also said that she was ‘aware of the wellbeing officers’ available at her hall.

However, both Joanne and Mimi knew far less about the financial services offered by UCL. Mimi told The Cheese Grater she was ‘vaguely aware because [she has] friends who are financially supported by UCL’ but that she had ‘never heard about it from any official UCL sources’. Similarly, Joanne also stated that she was ‘not aware of the financial support offered by UCL’ and that it ‘could be better publicised’.

Whilst SSW services are very accessible and students’ wellbeing needs to come first, the reality is that for those struggling financial support might be the only real solution and seemingly, some students would not know where to start if they ever needed it.

UCL Accommodation say they can ‘arrange a payment plan’ if you’re struggling to afford halls. UCL also has a Student Funding Advisor, a financial assistance fund and the SU’s Advice Service (amongst a few other schemes) for students struggling with financial issues. One might be inclined to think, though, that such services pale in comparison to the enormity of the renting crisis. No matter how well-intentioned, a payment plan or an employee at the student advice service are (understandably) not going to fix the debilitating effects the threat of homelessness and the inability to pay for other necessities is going to have on a UCL student who can’t afford to live in halls.

It’s no surprise then, that in the SU’s survey obtained by The Cheese Grater only 13% of students thought that the UCL’s financial assistance facilities are adequate enough to support students through financial issues.

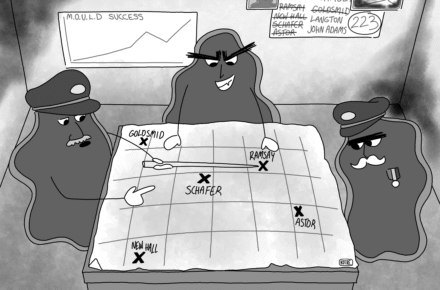

Renting doesn’t get much easier living outside of halls. For UCL students, this means entering a market that is stacked against them. As the NUS has said: ‘Landlords view students as fair game for exploitation as many have little to no experience of renting, creating a toxic power imbalance which leaves students with little control over their living situation’.

In order to glean the impact of flat hunting in London’s wild west housing market, The Cheese Grater also spoke to a number of UCL students in private rental accommodation to discuss how flat hunting had affected them and shaped their educational experience.

The students we spoke to found themselves insufficiently informed throughout the process. There is guidance offered by the university and the SU, such as housingadvice.london, (a comprehensive online guide published by UCL). However, these are often poorly marketed, with one student telling us she only found out about the University of London’s Housing Week after it had taken place.

Another student, Angel, didn’t realise there was guidance at all, saying: ‘I thought it was a fend for yourselves scenario’. Evidently the experience of flat hunting as a student must have felt more like being in a gladiator ring with lions than an organised part of adulthood. Angel added he felt ‘out of [his] depth’ and ‘certainly not that well informed’ when he first started looking for private accommodation. This suggests UCL needs to do more to promote its housing help, especially because a lot is already available. If it’s not publicised, it’s not aiding students and it just becomes wasted.

Maureen, an international student with no prior experience in renting tells us that she and her flatmates were ‘lost’ for two months as they ‘didn’t quite know what to expect’. Seemingly, UCL also needs to create more material dedicated specifically to helping international students who have no prior exposure to the UK housing market.

One option UCL does have available to international students is the Rent Guarantor Scheme in which UCL acts as guarantor in place of someone in the UK. However, Maureen explained that most landlords were having none of it and demanded that she instead paid 6 months’ rent upfront. Whilst UCL’s scheme is well-intentioned and with the potential to be very useful, students will only be protected if landlords will accept it. Having to fulfil the steep ask of 6 months’ rent upfront is yet another financial pinch on UCL’s international students who already have to pay so much more in fees.

Ultimately, UCL students described how all-encompassing the process was. Another student, Isabel, told us that ‘this is what I have been doing, all day everyday. I constantly have Rightmove and Zoopla and OpenRent open, calling immediately when things come on, and I’m already like number 25 on the list of people requesting a viewing.’

Flat-hunting in London clearly takes an exhausting toll on UCL students, particularly because many start around the end of exam season when they are already very busy. This is a problem unique to UCL as the issue of finding accommodation at universities in other cities typically comes much earlier in the academic year. Rightfully exasperated, Isabel decisively told us the market was just ‘insane and horrible’.

Trying to flat hunt alongside doing anything else – exams, internships, working or otherwise – whilst trying to maintain any sense of wellbeing seems almost impossible. Another student, Lewis, described the situation as a deeply ‘stressful experience’, akin to ‘a full-time job’. The experience of flat hunting clearly overrides the educational experience to the point that during flat-hunting season, studying at UCL is completely overshadowed by the distressing experience of actually trying to find a place to live.

Living in London has always been expensive, but Isabel tells us that she never expected things to get this bad when she first moved here five years ago. Back then, she said, ‘I looked at the people who pay £800 [pcm] for a room and was like, oh my god, they’re so rich […] they’re so close to uni and they have the best room. And now I’m begging somebody to accept me paying £1,000 [pcm], of which I’m paying 6 months upfront, to let me live anywhere.’

There’s certainly no exaggeration in this. Even the director of SpareRoom, Matt Hutchinson, was shocked by the skyrocketing rents on his own website, with a room now averaging £971 a month. In an interview with the Standard, Hutchinson said, ‘It wasn’t that far back that, when we got an ad for £1,000 a month, we sent it around the team and went: “look at this, it’s so expensive, who’s going to pay that?” Now it’s the average.’

Finally, The Cheese Grater had the opportunity to get a comment from Lucas Dastros-Pitei, the 2023/24 Students’ Union Accommodation and Housing Officer. He explained that he was ‘disappointed’ by the latest rent hikes and ‘understand[s] that the cost of living is causing plenty of issues and is leading to higher rent prices’.

Lucas clarified that ‘the financial assistance fund exists to aid undergraduate and postgraduate students who are estranged from family, have caring responsibilities and/or suffering from financial difficulty due to the cost of living crisis. UCL can award students in these groups with up to £3,000, a quarter of the full London based maintenance loan!’

In terms of the private rental market, Lucas told us that he knows ‘people take advantage of students (especially internationals) through scamming’ and that ‘in order to achieve a more equitable renting landscape, [he] believe[s] that bringing back rent control could protect tenants and students from excessively high rents and regulate landlords.’

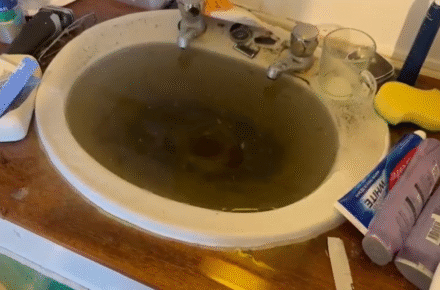

We can only hope that the government soon comes to share Lucas’ view as there is no other way to put it: London has become prohibitively expensive. Faced with the very real threat of homelessness or selling your left kidney to live in the equivalent of the Student Centre toilets, it’s understandable why so many students feel that living in the capital is a never ending scam for anyone who’s not a squillionaire.

UCL Accomodation is obviously not responsible for London’s soaring rent prices, but that doesn’t mean they can’t provide more help for students affected by them. UCL’s own rent increases are significant and whilst financial support services are on offer, the Union’s own surveys demonstrate that the overwhelming majority of the student body believe they are inadequate.

The university needs to better promote its housing assistance resources, especially for international students, and explore more affordable housing options. Addressing these issues is crucial to ensuring that students can pursue their education without the overwhelming burden of high living costs.