“If we had Muslims or people of colour holding the same conference … we would have seen counter-terrorism police on our doorstep the next day.” SU UCL BME Officer Ayo Olatunji was incensed by the news of the London Conference on Intelligence, held at UCL.

The now-infamous annual eugenics seminar, convened by an honorary senior lecturer at UCL, drew outrage and disgust when it was exposed by London Student in January.

Olatunji, together with Education Officer Sarah Al-Aride and Welfare and International Officer Aiysha Qureshi runs the Decolonise UCL campaign, with the threefold aim of reforming teaching and the curriculum, creating a more inclusive community, and redressing the legacy of racism at the university.

But in Olatunji’s estimation, the problem runs much deeper and its scope extends beyond UCL. He accused the Prevent strategy of effectively criminalising Muslims, interpreting mainstream religious beliefs as evidence of radicalism and incipient violence.

Of the conference, he complained that “Prevent didn’t know any of this was going on.” Prevent predominantly focus its attentions on student groups, especially those with large numbers of Muslim students.

Bella Malins, Lead Officer for Prevent at UCL, stated that “UCL has made no referrals under Prevent to the Channel programme”.

She further commented, “we are currently working on a training programme that puts awareness of unconscious and cognitive bias at its heart.

“The intention is to ensure that any preconceived views or unconscious bias that an individual may have can be addressed in a structured way as part of the wider training on Prevent.”

Scientific racism

The conference struck a particular chord because of UCL’s long and troubling history of racial science. “UCL has a legacy which other universities may not have,” Olatunji observed, save perhaps Oxford, Cambridge, and Liverpool.

UCL was the academic home of eugenicist Francis Galton in whose name a chair for eugenics was established in 1911. Other eugenicists such as Flinders Petrie and Karl Pearson worked at the university, and lend their names to buildings on campus.

Subhadra Das, curator of UCL Collections, has worked extensively educating people about UCL’s ignoble past. “UCL was ahead of the curve,” she acknowledges, “but the curve was pretty wide.” Plenty of other institutions, such as LSE, King’s College, and Imperial must reckon with similar histories.

Das rejects that tearing down the markers of UCL’s troubling past is a panacea of any sort. “If we take Galton’s name off the lecture theatre, there is nothing to talk about.”

Her project BRICKS + MORTALS provides a narrated walking tour of UCL’s campus, taking participants through the university’s hidden history of eugenics.

She asserts a need to deconstruct the idea that science is politically neutral in favour of reframing science as an ideology. There is insufficient discussion of racism as “a scientific construct”. And museums, she believes, are an ideal site to facilitate such discussion and pursue social change, a “space and a conduit for decolonial conversations”.

In the last fortnight, the Provost agreed to provide funding for the Centre for the Study of Racism. Vice-Provost Professor Ijeoma Uchegbu is currently working with faculty deans to appoint an academic lead. Three devoted academics will be assigned to work within the Centre for a period of three years.

In January, when Olatunji called for such a centre, it appeared some way off from becoming reality. It would seem then, that the London Conference on Intelligence and increased pressure from Decolonise UCL campaigners has spurred UCL to action.

Marcia Jacks, Institute Manager for Women’s Health and Co-Chair of the Race Equality Steering Group (RESG), said, with the announcement of the new centre, at least “some good came of [the conference].” She is pleased to see UCL “taking responsibility” — in a practical and symbolic way.

Dr. Michael Collins of UCL History, who works on decolonisation, welcomed the news as an “important step for the College”. Reckoning with UCL’s past, he argued, “goes well beyond just changing names and taking down statues.”

Certainly, symbolism is important. “I’m not ultimately averse to changing names,” but it should take place within a context of “challenging and questioning the ways in which we think about a whole range of human and hard sciences.”

Galton’s inheritance

In 2015, Provost Sir Michael Arthur jokingly offered the defence that the University had “inherited Galton”. But Olatunji’s work continues to challenge an intractable, institutional racism at UCL.

Olatunji feels an obligation to “be the agitator”. He occupies a unique position as a sabbatical officer — without the same restrictions and responsibilities that face academics and other staff working in this area.

It is a “very draining job”; he is the only full-time BME Officer at any British university, and has spoken at campuses around the country.

He feels that more positions like his are important but not alone a solution. Ultimately, this work requires a broader base for it to be successful. Many universities lack even a full-time Welfare Officer position.

Marcia Jacks’ work within the RESG has most recently comprised the development of a toolkit for teaching staff and departmental administrators to consult to overcome inequality in education and employment.

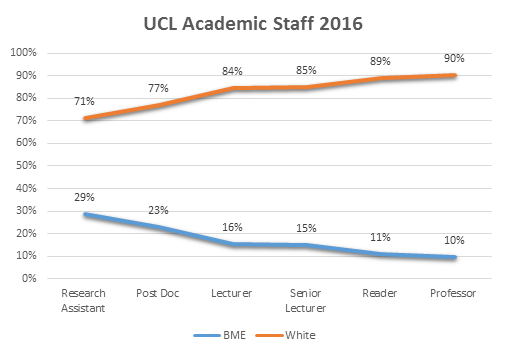

Of the 174 staff at UCL earning £140,000 or more per year, only 20 are BME; BME staff are more likely than white colleagues to be on short-term contracts; on average, white staff are promoted quicker than BME colleagues.

In 2015, UCL received a Bronze Race Equality Charter award.

The London Conference on Intelligence drew headlines, but racism on campus goes far beyond the high-profile and publicly scandalous.

In a recent focus group of BME students at UCL, one stated, “At the beginning of the year, the whole course were told that BME students always do worse in the practical exam. This was announced as a fact to everyone!”

Another shared that teaching staff mocked international students who would not understand that they were being made fun of.

One alumna recalled on Twitter that a professor in the English department was rumoured to have interviewed a PhD candidate with a row of golliwog dolls lined up in his office.

Marcia Jacks described being discouraged from applying for her present position by a colleague, as it would be “very competitive”, and “not for you”.

Most students have probably witnessed racially insensitive or inappropriate comments in the classroom. But the infrastructure for reporting is inadequate and, according to Olatunji, systemically biased against the student.

When the word of the student is pitted against that of a credited and professional academic, the outcome of the complaint tends to favour the academic. Even academics found guilty of making racist remarks are rarely punished severely.

In Olatunji’s experience, students suffer the most. In the aftermath of a complaint, some have faced academic reprisals and seen coursework marks decrease. The cases he knows are only anecdotal, but have created a fear of reporting racist incidents, which many students see as more trouble than it is worth.

With issues of racism, the relationship between UCL and students is characterised by a high level of distrust.

The establishment of an academic centre to study UCL’s role in propagating structures of racism and eugenics is laudable. But the struggle to build an equitable institution is ongoing.

Many people within the UCL community are working tirelessly to shine a light on the university’s shameful past and begin righting the sins of Galton. Victories like this academic centre are a step forward, but mustn’t be an excuse for complacency.

Peter FitzSimons, Jasmine Chinasamy and Elias Fedel

Featured image credit: Julian Coleman

A version of this article appeared in CG Issue 61.