Keziah Cho

On Charlotte Street one finds two households, both alike in dignity. Or at least that’s what UCL accommodation would have you believe. In fair Fitzrovia where we lay our scene, one hall reigns supreme, and it’s mine: Astor College. But look across from our hallowed door, and yonder lies the opposite existential plane: Ramsay.

As a proud Astorian, one question haunts me every night as I slice tofu in a kitchen with more open space than my seminar room: how do the Ramsayers live? The conditions of their habitat are an enigma. Every evening I mentally salute the Domino’s guy standing outside the gates and the pyjama-clad girl trudging out to meet him—both illuminated by the dystopian white light emanating from within. I ache to investigate, but the world within is off-limits. The turnstile bars all outsiders from the hall. Or are the hall-dwellers imprisoned within, too dangerous to be let loose? Ramsay is shrouded in a thick cloud of mystery, and the turnstile stands guard, as impassive as a lump of steel can be.

I’m on the point of calculating how high a jump would be required to hurl myself over the gates one afternoon when my friend Kylie invites me over. This is a pleasant surprise. I haven’t asked her about what it’s like on the inside, on the assumption that it’s bad etiquette to talk about Ramsay in front of the Ramsayers.

It’s the reverse prison break scheme of all time, because you can’t even tap in twice with your student card without tapping out first. She taps in, spins her way through the turnstile, taps out, then passes her card to me through the metal bars of the gate. I take the card. It feels heavy in my hands. This watertight security unsettles me. What alternate universes have they locked away in there? Will my mind bear the weight of this newfound knowledge? I imagine my Astorian comrades scoffing at this foolishness of mine as they recline in their velvet armchairs. But no, it’s too late. I tap in; the turnstile is deceived. In a flurry of old steel, I find myself in forbidden territory.

There’s a massive sign with arrows pointing to Rome, Paris, London, and New York—which, I am told, correspond to the four blocks surrounding us. I search in vain for an Oslo, or a Tbilisi, or even a token Ottawa. We push open the doors to Rome, where Kylie lives. At the foot of the stairs, lying at a 45-degree angle, is a toilet sink.

Upstairs, there’s a distinctly Roman architectural style (symmetry; all the doors are the same aggressive shade of blue), yet a distinctly less Roman aroma of strawberry vape, weed, and burnt-out gymbro soon envelopes us. I, however, am distracted mulling over what the inclusion of the fallen toilet sink could possibly mean. Avant-garde decor? An artistic lament for the fall of proper bathroom hygiene? Kylie interrupts my thoughts by ushering me into the kitchen.

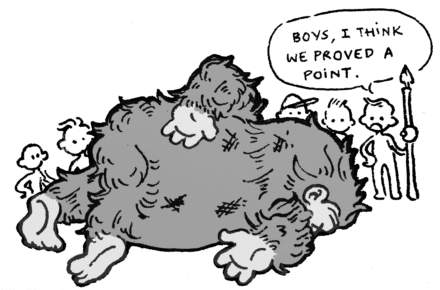

But something is deeply wrong. Where are the marble-topped kitchen islands, the high wooden chairs, the infinite shelf space? Ignoring my questions, Kylie plonks a solid brick of butter and a single bagel on the countertop. Resting in the drawer is a single teaspoon, which she draws out and stabs into the side of the bagel with the vehemence of Brutus disembowelling Caesar. Having mangled the bread to her satisfaction, she uses the same spoon to whittle away at the butter. I watch as curved slivers of butter fall from the block, onto the untoasted bagel half. The hole of the bagel stares back at me. In the back of my mind, a core memory forms.

Lunch à la Ramsay being over, Kylie says she’ll take me to the common room. We go past the endless rows of blue doors and the sink of the Roman baths. I think this must be it, but she continues leading me down into a network of empty underground paths. If the Ramsay common room exists, it’s not somewhere even a disembodied piece of bathroom apparatus would venture. I turn back towards what must be the way we came in. I look to escape, but it’s too late. Kylie urges us on. Left, right, sideways, at a 45-degree angle; all the paths look the same. There is no escape.

Outside, once again, someone has failed to enter; the buzzer’s alertly descending melody reverberates. I, too, am descending. But where? What else exists but these labyrinths of Parisian greige and New York cyan? I remember a coursemate calling Astor liminal. Too late, I only now realise where the True Liminal Space of UCL accommodation is. In the hole of the untoasted bagel. In the constant rotation of the turnstile. In the vortex of swirling clothes, clunking away in the Circuit machines. Something in me short-circuits.

I have discovered, at last, the void.