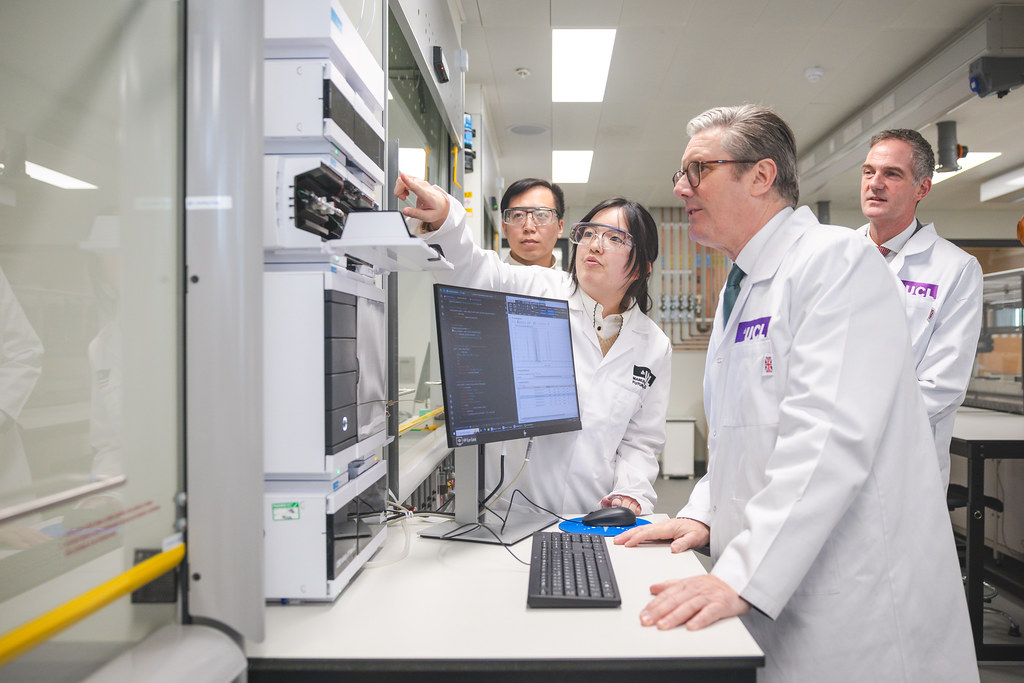

This week saw Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer grace the front pages of every major newspaper as he announced plans to make Britain an “AI superpower” from UCL East.

The Government’s AI policy was extensively reported by the national press, but UCL students may be wondering: what is it with Labour’s obsession with launching policies at UCL?

Not only did Starmer visit our East campus this week, but last month the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster Pat McFadden also used UCL East to announce the Government’s plans to reform the civil service by making it “more like a startup”.

It is clear that Starmer’s party loves a bit of UCL. The Government has used no other university more than our own to promote their agenda for the next four years, but why is this the case? What is it about UCL that makes it so appealing to New New Labour?

There are many reasons why Labour loves UCL, but one drives this institutional romance more than any other. As noted in an episode of Grater Insight, UCL appeals so strongly to Labour by virtue of the institution’s structure and its intrinsic similarity to Labour’s plans for governing. From the University’s technocratic research-based business model to its “disruptive thinking” in policy research, UCL encapsulates the political zeitgeist of this iteration of Labour politics.

Starmer’s affinity towards UCL goes back to his time as a front-bencher in Jeremy Corbyn’s shadow cabinet. In March 2017 Starmer, whilst Shadow Brexit Secretary, visited UCL’s Institute of the Americas to give the annual Eleanor Roosevelt Lecture on Human Rights.

Since the current PM became the leader of the Labour Party in 2020, various other Labour big whigs have visited campus and used UCL research in their Parliamentary speeches and policy plans.

Many of these politicians have drawn on the thinking of numerous Labour-adjacent public intellectuals who hold posts at UCL. Many of UCL’s most famous academics, such as the IIPP’s Professor Marianna Mazzucato and UCL Policy Lab’s Dr Marc Stears, are direct affiliates of Starmer and play crucial roles in the policy development process.

Such academic activity in the social sciences draws the Labour Party in on the side of policy. Naturally, the party of government has gravitated towards UCL as it is the institution where the greatest number of intellectuals developing novel ideas on progressive transformation can be found.

This is perhaps a chance phenomenon, but the concentration of Labour-adjacent intellectuals at UCL also speaks to the University’s central theme of “disruptive thinking since 1826”. Rather than deferring to the authority of Oxford or Cambridge – institutions characterised by their intrinsic conservatism – Starmer’s Labour is drawn to what they see as the progressive ethos and aesthetic of UCL as an institution.

It should be noted, however, that the PM’s love affair with his constituency’s university is nothing new in Prime Ministerial history; he isn’t even the first Labour Party leader to be heavily associated with the University.

Indeed, ex-leader Hugh Gaitskill was a lecturer in political economy at “the College” during the 1930s, and Tony Blair often frequented the University in the early 2000s – especially after the opening of the second University College Hospital in 2005, which was hailed as a “sublime work” of New Labour by the Guardian. Despite this, Blair’s time in Bloomsbury is perhaps most famously remembered by students jeering him during a visit in 2012. Regardless, it is still the case that no previous Labour leader has been as close to UCL as Starmer.

This closeness can perhaps be explained by UCL’s eastward expansion. Along with its social sciences faculties, intellectuals, and research having much in common with the policy inclinations of the Labour Party, UCL also boasts a STEM research output matched by few others in the UK. UCL East encapsulates this fact, with its high-tech robotics and AI laboratories providing an appealing visual backdrop for Government initiatives regarding the use of technology to improve public services. The University’s success in achieving great research output, generating £9.9bn for the UK economy in 2022, is a model which the Labour Party wishes to reproduce across the country to kickstart the nation’s economy after 14 years of Conservative leadership.

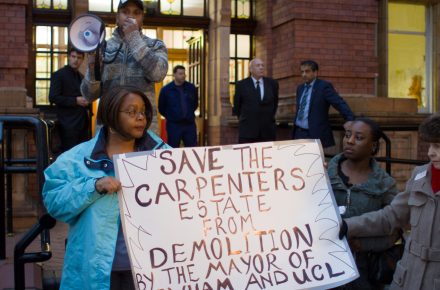

As noted, in opening the state-of-the-art facility in Stratford to foster more research and development, UCL has improved its global standings in research rankings – but this rise has potentially been at the expense of student experience.

Many argue that, whilst the University was able to raise £480m to build the new campus, struggling students have been given little direct fiscal support from UCL to lighten the burden of the cost of living.

This type of critique has also been levied against the Labour Party during their first few months in office by both students and the wider public. Many have questioned the Government’s lacklustre drive to improve material conditions for the British people whilst they have championed keeping corporation tax at the lowest rate in the G7 alongside committing to heightened defence spending, tuition fee hikes and implementing real-terms cuts to public services.

Ultimately, Starmer sees UCL’s progressive research and its contribution to the UK economy as the perfect advertisement of British success, a hard thing to come by in post-austerity Britain. UCL East is the physical embodiment of this vision, and explains why Starmer chose our Stratford campus as the home of his Labour party.

It’s either that, or he wants to avoid Bloomsbury at all costs, especially after what happened to Tony Blair last time he came to WC1.