Since its inception in 2012, UCL’s campus in Qatar has been a running sore for UCL management.

This will come to an end in 2020, however, following the university’s decision not to renew its contract with the Qatari Foundation which surprisingly fully funded the “twin campus” venture.

But to call UCL Qatar a campus is an overstatement. With approximately 85 students, the tiny establishment is located on the second floor of the Georgetown University building in Doha.

In its five years of operation, UCL Qatar offered four Master’s programmes, educated approximately 300 students and suffered at least two major, public scandals.

With this track record, one may wonder what UCL — which makes no financial contribution to their Middle Eastern satellite — hoped to gain from their close partnership with the Qatari government.

Selling the Family Silver

Hardly a flagship campus, UCL’s Qatari outpost is unusually distanced from the Bloomsbury headquarters. According to one former student, most, if not all, academic staff at the campus had never taught at UCL before coming to UCL Qatar, and UCL’s financial link is minimal.

The tiny campus is fully funded by the Qatar Foundation, owned by the Qatari royal family, which covers all operational and capital expenditure, including staff salaries. (UCL makes no direct financial contribution to its Qatari campus.)

However, the Foundation’s generosity does not extend only to the campus’s expenditure. Last year 59 of the approximately 85 postgraduates received either scholarships or bursaries from the Foundation, amounting to a total of 2.9 million Qatari Riyals (approx. £60,000).

The former student recalls that many received at least partial funding for their fees and accommodation despite suffering no significant financial hardship. Others had both covered in full alongside a monthly allowance.

The Foundation’s philanthropy may seem excessive or surprising. However, for the past decade the Qatari regime has sought to make itself palatable to Europe and America by pursuing a modern, liberal image. The Qatar Foundation is in part a means to this end.

According to UCL Qatar alumni, the education of Qatari citizens seems to have been the Foundation’s priority. While foreign students were in no way made to feel less welcome than their Qatari colleagues it remains questionable to what extent the Foundation saw their education as its primary aim.

Revealingly, two courses which reportedly attracted no Qatari students in two consecutive years have since been cancelled “in line with market demand and Qatar Foundation’s educational priorities, to support the development of Qatar’s cultural heritage sector.”

With no financial and little academic input from UCL proper, it appears that the Doha campus is little more than a franchise, leased to the Qatar Foundation to bolster the CVs of young Qataris.

Mo Money: Mo Problems

UCL signed the contract with the Qatar Foundation in 2010, and in 2012 became the first British university to open a campus in ‘Education City’, which already boasted international branches of such institutions as Georgetown University, Northwestern, Cornell and HEC Paris.

The Qatar Foundation is ostensibly a privately-owned non-profit organisation that aims to support the cultural and educational development of Qatar in order to transform the country into a “knowledge based economy”.

It was founded in 1995 by the then-head of state, Hamad Bin Khalifa Al Thani and his second wife, Moza bint Nasser, who is the leading force behind the foundation.

The organisation, while privately owned by the Qatari ruling family, also receives funds and support from the Qatari government. However, given the fact that Qatar’s Emir is both the head of state and government, it is hard to tell where his private fortune ends and public funds begin.

Guilt By Association

UCL’s choice to leave Qatar seems to be in line with its other policies, such as the Global Engagement Strategy and the 2034 Strategy which will see the closure of the other overseas campus in Adelaide, Australia.

UCL sees running full independent institutions as impractical, instead concentrating on co-operations and partnerships with existing overseas universities.

However, as early as 2014, UCL’s international vice-provost, Dame Nicola Brewer, said that UCL’s “relationships in Qatar need to be reviewed in light of a changed political context there”, referring, presumably, to Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad becoming the Emir in 2013 after his father, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa, stepped down from the role.

Tamim is known to be distinctly more religiously and socially conservative than his father, and some of UCL Qatar’s ex-students feel that he’d prefer to see the satellite campuses catering specifically to Qatari students.

UCL also has its reputation to think of: the Doha campus has brought UCL its fair share of scandals.

In 2014 Labour MP Alison McGovern urged UCL to reject slave labour and exploitation of migrant workers who were reportedly employed as gardeners and cleaners at the campus, and in 2015 The Times uncovered the extent of sexist employment practices at UCL Qatar, revealing that married female employees received considerably less housing support than married men.

In one case a male employee was paid £3,568 compared to the £624 awarded to a female staff member just one pay-grade below him.

In both cases UCL excused itself by shifting the blame onto policies adopted by the Qatar Foundation.

After UCL has retreated from the Gulf, all their courses at the Doha campus will be transferred to the all-Qatari Hamad bin Khalifa University.

Some may wonder whether educational freedom can be reconciled with the mores of an autocratic regime. UCL’s departure from Qatar, suggests that the management at Bloomsbury don’t think so.

Weronika Strzyżyńska

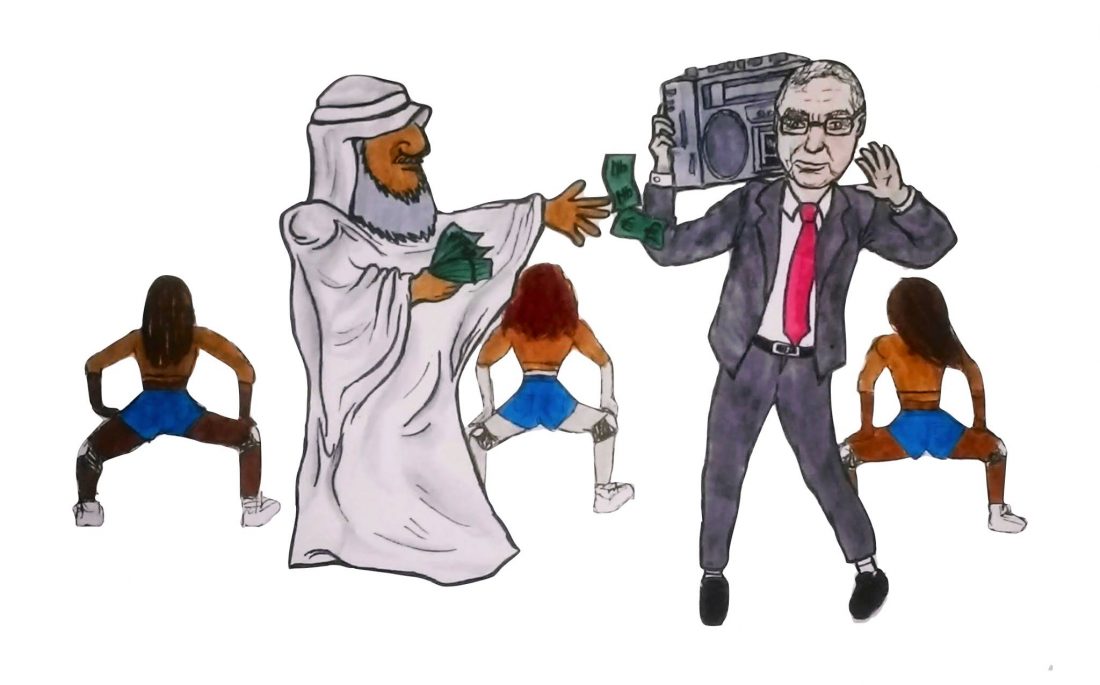

Artwork by Anna Saunders

A version of this article appeared in CG Issue 58.