Everything Pi Mag’s patriarchal history of the spud didn’t tell you.

Is there a more radical food than the potato? I would argue no. Most people don’t know about the secret role of the humble potato in the women’s movement. From the underwhelming beginnings of looking a bit like a boob, the potato became the catalyst for subsequent waves of feminism all over the world.

It is a little known fact that potatoes were invented by matriarchs in South America so that they would have something hard to throw at unruly men. Some fuckmen then stole the potatoes and delivered them to Europe, where everybody started eating them, despite them clearly having very little nutritional value and being blatantly inferior to the sweet potato, from which the potato derived its name.

Peasant women found that they could hide potatoes under their dresses so that hungry men couldn’t steal them, claiming they were just a part of their naturally lumpy bodies. It was in this way that potatoes became fashionable. An aristocratic woman was touring her father’s estates when she noticed the lumpy bodies of the farmhands. When she realised that the women were hiding potatoes under their smocks, she devoted her life to digging up potatoes to spread to all of the women in the land, and was thereby known as “Lumpy Spade Princess”.

At the height of its popularity, the potato occupied much of the same cultural space as the avocado does today: people tried to smush it on bits of bread, it wasn’t very nice in salads, and people got quirky tattoos of it. The rapid growth in population in the mid-19th century can be attributed to the potato, because the skin of the potato contains the compound mmmyeahimhorny, which stimulates the cells in the body to become subject to the gravitational force of electromagnetism that emanates from men’s egos.

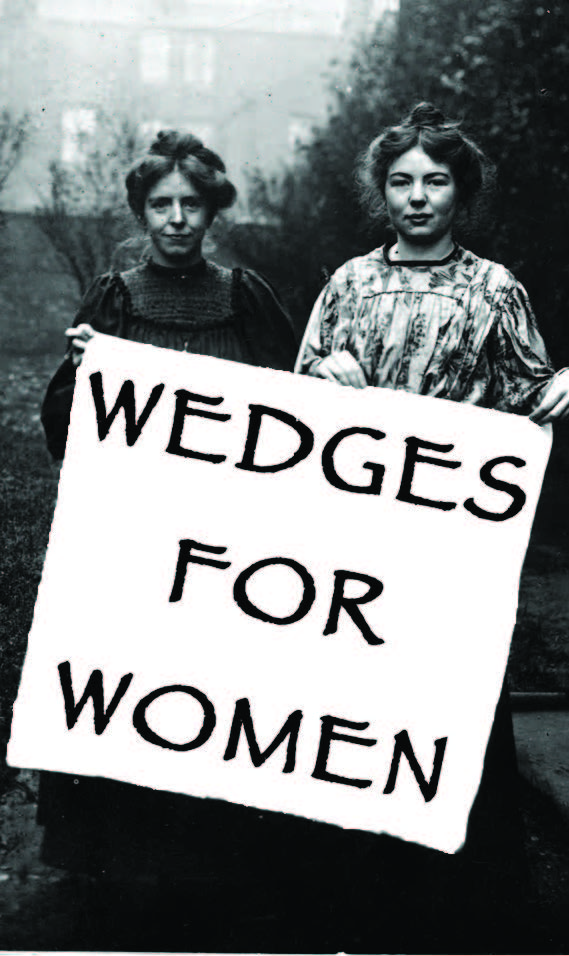

The herstory of the potato is particularly important for Marxist feminists, because rumour has it that Marx invented communism only after a potato hit him on the head. Fast forward to the 20th century, and we can see what a vast impact the potato had on the modern women’s movement. While on hunger strike, suffragettes hid crisps down their pants in case they got too peckish. Some sources even suggest that when Emily Davison threw herself under the King’s horse she was just chasing a potato that was rolling down the street.

Feminist historians emphasise the importance of potatoes during WWII. While their husbands were away, women instead shared their beds with sacks of potatoes and found that unlike men, they didn’t make a mess or fart in bed. The 1950s arrived and women were chained to the kitchen, making chips, potato dauphinoise and mashed potato. A little known fact is that the tendency for these foods to be served with salt originated with the tears that women would spill into the food as they were coerced into constantly cooking.

The swinging sixties swung around and women burnt their potatoes in protest of the patriarchy. The men missed their chips so much that they invented the pill to let women choose whether to have children. This way they had time to both make chips AND fight for equality.

Potatoes ceased to be important in feminism until the 1990s, when third wave feminism struck. A central tenet of the third wave was that diverse women with ranging tastes in potato-based foods should be incorporated into the feminist agenda. The term itself was coined by academic Rebecca Walker, who was of course the heiress to the Walkers crisps empire. A battle broke out between second and third wave feminists, the second-wavers led by Germaine Greer, who maintained that bubble and squeak was an abomination.

The third-wavers were much more accepting of all potatoes and eventually won the war by besieging the secondwavers, who quickly ran out of food because of the limited varieties of potatoes that they would consume. Today, the potato is rightfully recognised as the most socially reformist food of the modern era, and the modern women’s movement is built upon it. To quote Lena Dunham, “If I have seen further than most, it is by standing on the shoulders of giant potatoes. And also by ignoring pesky women of colour.”

Who would’ve thought that the humble potato has been radical, emancipatory and fried?

Maris Piper

This appeared in CG 53.